TALLAHASSEE — The bombshell landed a day before Florida’s nationally watched 2018 midterm elections.

A Quinnipiac University poll showed two statewide Democrats, Sen. Bill Nelson and gubernatorial candidate Andrew Gillum, seven points ahead of their Republican opponents.

The numbers signaled a political upheaval in the nation’s largest swing state: The ascension of Republican Rick Scott, who was running for the Senate after two terms as governor, would be over, and Democrats would hold the governor’s mansion for the first time since 1999.

But when it was over, three things were true: Scott won. Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis won. And Quinnipiac — once again — lost.

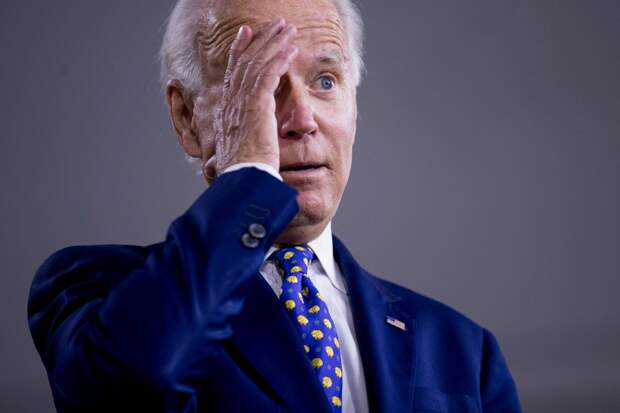

Now, as the presidential election heats up, the nation’s largest swing state is snubbing the marquee pollster. When Quinnipiac dropped a survey last week that showed former Vice President Joe Biden up 13 points over President Donald Trump, Florida didn’t flinch.

“I don’t even look at them anymore,” said Ryan Tyson, a veteran Republican Florida pollster and founder of The Tyson Group, which works with both political parties. “They are not really tied to reality.”

The Hamden, Conn., university has built an outsized reputation as a go-to public polling pro. Its eagerly anticipated surveys hijack cable TV news chyrons, are dissected by talking heads, and can help cement a state-of-play narrative in important campaigns.

But in the battleground state of Florida, which is bracing for what could be a bruising and close presidential election, Quinnipiac’s polls are being met with a shrug. Or an eyeroll.

In a statement, Quinnipiac defended its techniques and noted its predictions had come within 2 points of the winner’s margin of victory in the 2008, 2012, and 2016 presidential elections.

But getting 2018’s top-of-ticket races wrong was just one example. After a series of recent flubs, the Q-Poll’s reputation among Florida politicos and news outlets has been eroding. Florida no longer trusts the Q-Poll.

“It’s three letters: Meh,” said longtime Florida Republican consultant David Johnson. On the plus side, Quinnipiac has united Florida’s professional political class, Republicans and Democrats, on at least one issue.

The skepticism was on full display last week when Quinnipiac released the poll showing Biden topping Trumpby 13 points among self-identified registered voters, a lead that would represent a landslide win in a state where skin-of-the-teeth victories are the norm. Florida had three statewide recounts in 2018 and its past two presidential elections were decided by roughly a single point.

Even Biden’s allies scoffed at the data. Florida Democratic consultant Steve Schale, who is working for a pro-Biden super PAC Unite The Country said Biden might be leading Trump by between five and seven points. The state’s demographically entrenched electorate means presidential campaigns in the state will always be tight and bitterly fought.

“Here’s the reality in Florida – our election and our electorate are very consistent,” Schale said.

The July 23 poll also showed a 42 percent approval rating for DeSantis, with 53 percent of self-identified registered voters disapproving, a massive reversal from where Quinnipiac’s polling had put him just four months ago, with a 53 percent approval rating.

DeSantis’ response to the coronavirus outbreak has drawn widespread criticism and many people believe it’s hurting his numbers. But not even Democrats believe the Republican governor’s fall has been that steep.

“For whatever reason, the Q-Poll seems to miss the mark more often than not, and typically in a way that breaks our Democratic hearts,” said Dan Newman, a Florida Democratic consultant.

Quinnipiac isn’t the only public polling institution to draw fire in recent years, but it has faced scrutiny because of its reach and impact. Public perception of polling in general has deteriorated amid societal changes — the loss of land-line telephones is one example -- and the rise of a less-predictable electorate.

That dynamic is only increasing as the end of the 2020 election cycle fast approaches

“Many of the universities have similar issues,” said Johnson, the GOP consultant. “They have political scientists who want to teach students how to poll, and that’s a really good thing. They just often do it wrong.”

Flawed polling can have a profound impact. Voter turnout can be influenced, for example, if people think a candidate has enough votes to win handily — or no chance of winning at all.

The Quinnipiac quandary is particularly difficult because its numbers influence how the media reports on a political horse race.

Schale used the example of the Quinnipiac poll that had Biden up 13 points. If a later poll shows Biden ahead by, say, four points, “the media will go ‘See, Trump is surging in Florida, he has cut nine points off the lead,’” Schale said. “Even though nothing has likely changed.”

Schale pointed to a Quinnipiac poll early in the 2012 general election that had Republican Mitt Romney topping then-President Barack Obama by six points in Florida. It created a narrative in a state Obama won that Schale said never existed. The university’s final 2012 poll showed Obama 1 point ahead of Romney.

“They released an early poll having Romney up six and suggested the state was solidly in Romney hands, when again, no internal polling showed anything like that,” said Schale, who worked on both of Obama’s Florida campaigns.

Doug Schwartz, associate vice president and director of Quinippiac polling, defended his university’s work, including in recent Florida presidential races, and doubled down on the university’s motto.

Our “gold standard methodology has proven accurate in every presidential election in Florida from 2004 to 2016, as Quinnipiac University polls came within three points of the winner’s margin of victory,” Schwartz told POLITICO in a written statement. “Looking at the last three presidential election cycles between 2008 and 2018, Quinnipiac University polls came within two points of the winner’s margin of victory.”

So what’s wrong with Quinnipiac? Florida pollsters say it starts with data that some pollsters don’t use.

Like many states, Florida maintains voter files that record who is registered to vote, their party registration, if any, their race and how often they cast a ballot. Because Florida has partisan registration and tracks the race of registered voters, its voter file offers more information than some other states.

The information allows pollsters to build polling samples tied to a state’s demographic makeup and historic political performance. But it’s information that Quinnipiac and other public pollsters don’t use.

“For the life of me, I just do not understand why they don’t use the voter file,” Tyson said of Quinnipiac. “It makes no sense. Florida makes available a lot of things other states do not, yet they choose not to use them.”

Quinnipiac instead uses random digit dialing, calling computer-generated phone numbers rather than the numbers of registered voters. While voter files are generally considered comprehensive, some public pollsters worry that phone information might not be available for all voters.

But random digit dailing can produce results that are less stable, especially if the pollster doesn’t adjust the sample for party identification. In the poll showing Biden with a 13-point lead, for example, the share of the sample that identified as Democrats — a different measure than party registration — was 6 points higher than those who identified as Republicans, a margin that even the most optimistic Democrats do not expect in the final turnout reports.

Schwartz defended the use of random digit dialing even in a state with reams of publicly available voter data.

“Random digit dialing gives pollsters the ability to talk with everyone,” he said. “When just relying on registered voter files, there can be coverage error when a voter cannot be matched with a phone number and therefore, cannot be included in the poll.”

Pollsters have long debated the merits of random digit dialing and voter files. As an example of random digit dailing’s success, Schwartz cited the 2017 Virginia governor’s race, in which Democrat Ralph Northam defeated Republican Ed Gillespie. Quinnipiac was the only poll to precisely measure Northam’s margin of victory, he said.

Of the 924 self-identified surveyed, 28 percent identified as Republican, 34 percent as Democrat, and 33 percent as independent. That sampling shifts from poll to poll, which is part of the Quinnipiac’s problem, some experts said.

And Quinnipiac and other public pollsters typically use few filters, variables used to select which voters they survey. Polling registered voters as opposed to likely voters is one common practice. Quinnipiac, like many other public pollsters, does not begin to identify likely voters until late summer, closer to the election.

When Quinnipiac does begin screening for likely voters, it generally relies on respondents’ answers to questions about whether they intend to vote or have voted in the past. Polls that rely on voter lists have actual turnout records, which are typically accurate, at their disposal.

“Do they turn out to vote in primary election or just general elections? Do they turn out in every election? Those are what I call ‘vote or dead’ people. They will vote unless they are dead,” Florida Democrat consultant and pollster Screven Watson said. “All these factors are important in determining a poll’s ultimate accuracy. Did your poll screen, and your modeling accurately predict who ultimately votes in a given election?”

“Any poll that uses ‘self-identified’ registered voters with no screen for their voting history is quite simply garbage,” Watson said.

Tyson said he sometimes will monitor Quinnipiac’s non-political polls, which are less reliant on nailing a partisan sample. Quinnipiac’s July 23 poll, for instance, found 81 percent of people believe wearing masks is an effective deterrent to the spread of coronavirus.

“They were generally spot on with the mask number,” Tyson said.