Elizabeth Warren was in the president’s head.

From the summer of 2010 through summer of 2011, the usually unflappable Barack Obama spent long hours agonizing over the then-Harvard Law professor – so much that his aides felt it was distracting from more pressing national concerns, according to interviews with numerous former White House officials.

Warren had become an unlikely star of the left amidst the financial crisis with unambiguous moral outrage and an ability to explain complex financial topics in ways that made them fodder for dinner-table conversation. Improbably, she had turned a largely powerless congressional panel monitoring the bank bailout into a national bully pulpit of populist fury. Her target was not just the big banks but the new Democratic administration which she suggested had been co-opted by them.

She parlayed her newfound status into a push for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to be part of the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill. As the legislation was about to pass in June of 2010, Warren met with the president’s adviser David Axelrod and was blunt: she wanted Obama to nominate her to run the agency or she could continue probing the Treasury department’s every move.

“I took it as a message, I think she meant it as one,” Axelrod says. Warren sent the signal that she could either be inside the tent pissing out or outside pissing in, Axelrod says, quoting a vivid Lyndon Johnson quip.

Obama was equally straightforward. “Tell her to keep her mouth shut,” he said, according to Axelrod. “She may well be the choice, but we can’t surface that now.

”Even though she had infuriated many on his own economic team, Obama did want Warren inside the tent. After he signed the Dodd-Frank legislation in July of 2010 with her in the front row, Obama tried to find a compromise.

One White House official suggested to Warren that the president would nominate someone else but she would be the bureau’s “cheerleader.”

“It was insulting. And I wasn't going to do it,” Warren recalls in an interview this summer from the presidential campaign trail in Iowa, dodging whether she found the suggestion sexist.

What about a special adviser? No. The bureau’s public spokesperson? Nope.

Obama then tried to make the personal sell. On a sweltering day in September of 2010, they met in the Oval Office and Obama took her to a private garden to pitch a vague role setting up the agency under Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner. With Obama cool in his shirtsleeves and Warren sweating in a jacket because she felt her shirt underneath was too revealing for a presidential audience, she again said no.

“I was not going to set that agency up asking Tim Geithner every day ‘Mother may I?’” Warren says now. “It just wasn't going to work.”

'That's not a success'

As Warren campaigns to become the 46th president, she doesn’t mention the 44th very much.

When she does, it’s usually to praise him. Asked in April at a CNN town hall what their main philosophical difference was, Warren did not name any. “You know, I'm going to take this in just a little bit different direction, if I can,” she said and then gushed about Obama’s steadfast support for the CFPB. “I will always be grateful to the president for that,” she said.

But interviews with more than 50 top officials in the Obama White House and Treasury Department, members of Warren’s inner circle at the time, and Warren herself, reveal a far more combative relationship between her and the administration than she usually discusses on the campaign trail. Tensions between Warren and Obama were palpable to White House aides, even as she reserved her real fury for Geithner and White House National Economic Council chief Larry Summers, whom she regarded as predisposed towards big banks over families struggling to save their homes.

For Warren herself, the years of the financial crisis are now the touchstone of her political career, validating the conviction at the heart of her presidential candidacy: that the system is rigged.

The acrimonious differences between Warren and her allies, and members of the Obama team, led in part to her decision, with prodding from Obama himself, to leave the administration to run for the Senate rather than continue pursuing the leadership of the consumer-protection bureau. But they never fully abated, and now represent dueling approaches to Democratic economic policy-making, presenting the possibility that the next Democratic president will have ascended to the height of Democratic Party politics in part by bashing the previous one.

Thus, while former Vice President Joe Biden often boasts on the campaign trail that his and Obama’s efforts saved the economy from another Great Depression, Warren regards the Obama administration’s top-down response to the financial crisis as part of the reason a man like Donald Trump won the White House eight years later.

“I believe the recovery should have been from the ground up, and people with Geithner’s and Summers’ background would never see the world that way -- they just don't see it that way,” Warren says. “America works great for the wealthy, and the well-connected -- that was demonstrated big time during the financial crisis...Donald Trump stepped into that, and said, ‘If your life isn't working great, blame them.’ His version of ‘them’ is anyone who doesn’t look like you.”

As for the Obama team’s arguments that the financial rescue was a success -- the bank bailouts ultimately made a profit, a depression was averted, and GDP growth resumed faster than the aftermath of most financial crises -- Warren considers them obscene self-congratulation.

“Sure, the banks are more profitable than ever, they are bigger than ever, the stock market is through the roof,” she says. “But across this country, there are people who still pay the price for a financial crisis that they didn't cause and that they never had a

chance to survive….That's not a success.”

‘Why are you pissing in our face?’

In Warren’s mind, the administration’s priorities were simply out of whack: banks were getting more attention than people.

The Obama Administration felt more urgency to save the large financial firms than to prevent home foreclosures.

“When I raised it with Tim, he reassured me that they'd done the calculations and it was all going to work out. And what he meant was the survival of the banks,” Warren says, recalling a meeting in the Treasury building in the fall of 2009. “He says ‘We’ve foamed the runway -- enough that the big banks can land.’ And the fact that millions of families were losing their homes, that millions of people lost their jobs, you know, savings, just wasn't part of that calculation.”

Some White House officials also brought concerns about foreclosures to Geithner, and his perspective was that saving the financial system was the necessary first step. Stabilizing the housing market was like bringing down unemployment in that “it will trail,” Geithner explained, according to Axelrod’s memoir, Believer.

“Yeah, exactly,” Warren says now, scoffing. “That's how they thought of it.”

Summers bristles at the attack on him and Geithner.

“Everyone had the same objective of preventing a Depression,” Summers told POLITICO in a statement. “Without saving the financial system we did not think that was possible. The one time when the no bailouts strategy was tried — with respect to Lehman [Brothers] — it was a catastrophe.”

Despite attempts to gloss over past disputes by focusing on areas of mutual agreement like the CFPB, simmering bitterness remains between Warren and large swathes of the Obama administration. In interviews, many former White House and Treasury officials say they consider Warren a self-serving grandstander who cast them as villains while they were trying to save the global economy from catastrophe -- a job they think they did pretty well, all things considered.

Geithner, who declined to comment for this story, wrote in his memoir Stress Test that he felt Warren “was better at impugning our choices -- as well as our integrity and our competence -- than identifying feasible alternatives.” He added that “[h]er criticisms of the financial rescue, if well intentioned, were mostly unjustified.”

Other Obama administration officials call her a “professional critic,” “sanctimonious,” and a “condescending narcissist.” As one former Treasury aide put it: “We’re with Barack. We’re the liberals. Why are you pissing in our face?”

“She loved herself and some of her staff had a God view of her and that’s not aligned with government and bureaucrats which require teamwork.”

—Obama Administration Official

One of the administration officials adds: “She loved herself and some of her staff had a God view of her and that’s not aligned with government and bureaucrats which require teamwork.”

People who worked closely with Warren at that time but who are not on her presidential campaign are equally scathing about Obama and his team.

“Tim and Larry and those guys, they are the villains of the Woody Guthrie song,” says one, a reference to the lyric “Some will rob you with a six-gun, And some with a fountain pen” in ‘Pretty Boy Floyd.’

“Obama called the bankers ‘fat cat's once and spent seven years feeling bad about it,” ridicules another.

“The Treasury crew especially thought they were the smartest guys in the room and the attitude was ‘We’re saving the world, what the fuck do you want with us?’ ” says one more.

It was amid these fights with the economic team that Obama wrestled with what to do with Warren’s request that she head the CFPB (Obama, through his spokesperson, declined to comment on his relationship with Warren). Senate Republicans and even some Democrats were adamantly opposed and Obama’s political team said getting the 60 votes necessary for her confirmation would be almost impossible. Plus, some in the administration worried about having such a political lightning rod in charge of a new agency trying to establish itself.

Liberals, who were already frustrated with Obama, were clamoring for him to nominate her. At the same time, some members of his administration despised Warren and wanted nothing to do with her.

Obama was conflicted. The 2010 midterms were coming fast, the economy was still struggling, the most ambitious climate change bill ever to pass the House had stalled in the Senate, and myriad other issues loomed. But top administration officials remember Obama spending an inordinate amount of time going back and forth about what to do with Warren.

Then-Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel, with an eye on the elections, became frustrated with the time-suck and recalls telling top officials that “the idea of financial reform, banking reform is a lot bigger than one office and one person,” emphasizing it had nothing to do with Warren herself.

Valerie Jarrett, Obama’s close adviser, acknowledges that “we did spend a lot of time talking it through” but says she thought it was merited given the importance of the bureau.

“She was someone whose name came up a lot,” Axelrod allows, referring to Warren.

“It was really eating away at him,” Geithner wrote.

Obama found a temporary middle ground in September of 2010 -- naming Warren as an assistant to the president and a special adviser to Geithner with significant autonomy to staff the agency while delaying the decision on who to nominate as director.

Several months later, the White House embraced a more permanent fix: have Warren run for the Massachusetts Senate seat that Democrats had lost to Republican Scott Brown and nominate someone else to head the CFPB. “It wasn't just an elegant way to solve the one problem, it was a really appealing way to solve the other, which is how to get that seat back,” recalls Axelrod.

Jarrett remembers she “drew the short straw” in being tasked with bringing the idea to Warren. That’s because she had been a Warren ally in the White House during the CFPB deliberations and retained a sense of respect for her, even while acknowledging that she “broke a lot of eggs.”

“It didn’t go so well, initially,” Jarrett says with a laugh, recalling her efforts to persuade Warren to give up personal control of the consumer-protection bureau. “It’s your baby and she wanted to see it grow up so I understood completely why she would have reservations about changing course.”

At Obama’s direction, Axelrod, who lived in the same apartment complex as Warren, met with her and her husband privately and encouraged her to make the Senate run. Sens. Harry Reid and Chuck Schumer lobbied her as well and promised to help her assemble one of the most experienced campaign teams money could buy. With a national profile that could help her raise money, Warren was an ideal recruit for the Democrats’ top Senate target in 2012.

As Obama and Warren both mulled what to do in early 2011, Rep. Barney Frank of Massachusetts -- who worked closely with Warren during the passage of the financial reform legislation -- got the president’s ear at a photo op and encouraged him to nominate Warren for the CFPB anyway.

“I said, ‘Well it’s a win-win. Either you appoint her and she gets confirmed. Or she is rejected and she wins the Senate seat,” Frank recalls. “And he said, ‘Do you think she wants to be a senator?’ and I said ‘I think she wants your job but she’s go to start somewhere.’”

“And he said, ‘Do you think she wants to be a senator?’ and I said ‘I think she wants your job but she’s go to start somewhere.’”

—Former Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.)

Frank ended up being right. As Obama increasingly shied away from nominating her to lead the CFPB and others lobbied her on the Senate run, she warmed to the idea, recognizing the potential power of the senatorial pulpit.

In July 2011, nearly a year after he signed the Dodd-Frank bill and after Warren had spent 10 months standing up the agency in a way that even impressed some critics in the Treasury Department, Obama took the middle ground. With Warren by his side, Obama nominated former Ohio Attorney General Richard Cordray to lead the CFPB. That same day, progressives called on her to make the Senate run. Less than a month later, Warren began a “listening tour” back home in Massachusetts to explore it. The field thinned and no other big-name candidate stepped forward to challenge her. She promised she wouldn’t go back to D.C. just to be the “100th-in-seniority, be-polite-and-make-no-difference senator from Massachusetts.”

Before going back to Massachusetts for the Senate run, Warren met privately with Obama one last time. “It was hot! He liked to be outside for these meetings,” she remembers, bemused.

They discussed a bit of everything but Warren says she urged him to surround himself with more people who she felt understood the level of anger in the country. “That’s how I saw it. That this crisis is not over,” she says.

“That the survival of the big banks is not the measure of recovery.”

"You guys are on the same team?"

Warren said yes before she understood the job.

It was November 2008. Obama had won the presidency days before. Reid, the Senate majority leader, called to offer Warren – comfortably ensconced in her teaching position at Harvard Law School -- a part-time job on a 5-person oversight panel charged with monitoring the $700 billion bank bailout known as TARP.

On paper, the panel was mostly useless. The legislative text tasked it with writing a report every 30 days and allowed it to hold hearings but didn’t give it the power to subpoena witnesses.

After saying “yes” to Reid, “I remember reading the, what is it like four lines, and I thought, ‘Whoa, that's it?’” Warren says.

With little statutory power, Warren plotted out another strategy: Be loud.

She had experience with that approach. During the decade-long battle over bankruptcy code reform that ended in 2005, Warren says, she learned how to create political leverage for herself and her cause through the media.

“I was so naive at the beginning, I thought ‘All I have to do is explain it,’” she recalls of her initial work with Congress on bankruptcy first on the National Bankruptcy Review Commission in the ’90’s and then as a Harvard professor in the early 2000s. “I started to understand in that process, how the only way to get Congress on the side of families that were broke was to bring public pressure on them. So in that space of time, during the ‘Bankruptcy Wars,’ I must have spent a million hours on the telephone with reporters starting with ‘B is for bankruptcy.’”

She testified before Congress, wrote op-eds blasting legislators including then-Senator Biden, and became an early entrant in the progressive blogosphere with “Warren Reports,” a group blog hosted by an offshoot of Talking Points Memo. She called lawyers looking for clients who showcased problems with the financial system whom she could then provide to reporters. “If you've got no stories to tell, there are a lot of reporters who won’t talk about it,” she explains. “And if the reporters won’t talk about it, then the world isn't going to hear about it.”

So when she returned to D.C. in 2008 and became chair of the oversight panel, the mandated monthly report became a monthly media tour. It would begin before dawn with an aide bringing her an Egg McMuffin but no coffee (“Can you imagine me on coffee?!,” she once explained to an aide who asked how she didn’t drink it.) Warren talked to everyone. She bashed the banks and the Obama administration on Fox and Friends, in The New York Times, and in Michael Moore’s 2009 documentary Capitalism: A Love Story.

The oversight panel and its few dozen staffers were relegated to the Government Printing Office where mini-forklifts, easy-to-assemble furniture that would occasionally collapse, and boxes of printer toner made up the workspace.

But the location came with access to Senate Recording Studio. Warren surprised members of her own staff by producing monthly videos of herself explaining each report. She and aides also created a comprehensive website with a regularly updated “blog.” Commonplace now, these digital tools weren't being used by many members of Congress in 2008.

Going so public was also a way to “start plowing the ground for the legislative changes that I knew were coming because every day that the stock market dropped I’d think about: ‘So, Congress is going to have to act. What are they going to do?’ ” Warren explains.

She also criticized Obama directly, telling author Ron Suskind at the time that she didn’t know why Obama was making certain moves because “He meets with bankers. He doesn’t meet with me.”

Her national profile reached the point-of-no-return in April 2009 after an appearance on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. “That is the first time in six months to a year that I felt better,” Stewart said after she summed up the financial crisis. “I don’t know what you did just there but for a second that was like financial chicken soup for me.”

Her most sensational moments, however, were when grilling Geithner. The new Secretary of the Treasury had been president of the New York Federal Reserve in the lead-up to and during the worst of the financial crisis. Obama believed Geithner’s selection would help ensure stability across administrations while the financial system was on the brink of disaster whereas Warren saw it as putting the people who helped create the crisis in charge of solving it.

A former student once dubbed Warren’s teaching method as “Socratic with a machine gun,” and in 2009 and 2010 Geithner was at the end of the barrel. Her questioning was so brutal at times that it stunned some of the Republicans working on the oversight panel.

Before a 2010 hearing about the status of TARP, Warren and Geithner made friendly small-talk in the anteroom, remembers Ken Troske, a conservative economic professor at the University of Kentucky on the oversight panel’s staff. “Then we get into this hearing then she climbs down his throat in ways that are extraordinary,” he recalls. “I mean, you guys are on the same team?” he remembers asking himself.

“You set aside 50 billion dollars and what do you have to show for it?"Warren demanded of Geithner at the hearing.

“The point is they ultimately lost their homes. So what is the metric for success here?” she added.

“Time is also running out to make certain that TARP money is used to help families and small businesses the way it was so quickly used to help Wall Street,” she pressed him at the same hearing.

"It seems clear that Treasury's efforts to reduce mortgage foreclosures is not working," she said.

"I'm losing the logic here, Mr. Secretary," she said at another hearing.

“A.I.G. has received about $70 billion in TARP money, about $100 billion in loans from the Fed. Do you know where the money went?” she asked at one, betraying a slight smirk as she did.

Such scenes made an impact.

“It was a viral thing,” Axelrod acknowledges.

Geithner accused her of distorting the truth and defended his actions. “There is no job growth without economic growth, no economic growth without access to credit, no access to credit without a stable functioning financial system and our emergency programs played an essential role in starting that process of recovery and repair,” Geithner said.

Many in the White House felt Warren’s critiques were righteous but dumb and following them would have hurt the very people she claimed to be championing. Geithner later wrote that “her TARP oversight hearings often felt more like made-for-YouTube inquisitions than serious inquiries.”

“One thing about her conversations with Summers and with Geithner, they couldn’t talk over her head.”

—Former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.)

But making them for YouTube and a wide swath of people was precisely the point.

“When Elizabeth was as blunt and direct as she was in standing up to Geithner in those hearing, people in the progressive world were electrified by it and heartened that someone was willing to stand up to a Democratic White House,” explains Mike Lux, a longtime Democratic operative who was an ally of Warren’s during the financial crisis.

As Obama positioned himself between the bankers and the pitchforks and took a hard turn from campaign poetry to governing prose, Warren’s furious rhetoric filled a populist void that many on the left had hoped Obama would occupy. Her response to the financial crisis led New York Magazine to declare in 2011 that “in large swathes of blue America, Warren’s star actually eclipses Obama’s.”

Reid, who appointed Warren to the oversight panel and has been an admirer of her presidential run, says he thought Warren clashed so fiercely with Geithner and Summers in part because she understood financial markets well enough that they couldn’t condescend to her.

“One thing about her conversations with Summers and with Geithner, they couldn’t talk over her head,” says Reid, adding that Summers, a former Treasury secretary himself and president of Harvard University, wasn’t used to that. “I met with Summers many, many times and, frankly, he talked about a lot of things I didn’t quite comprehend. But with her, that wasn’t the case.”

“Honk if I’m Paying Your Mortgage”

But some of their ideological differences were also rooted in their divergent backgrounds.

Geithner’s upbringing was “very privileged” as he writes in his book. Self-deprecatingly, he admits to being waitlisted at Wesleyan and Williams but accepted at Dartmouth in part because he was a legacy student. He then worked for Henry Kissinger in the private sector before ascending to the upper echelons of the Treasury Department under the tutelage of Treasury Secretaries Robert Rubin and Summers, who himself was the son of two Ivy League professors. Geithner flew around the world responding to macro financial crises and then served as president of the New York Fed from 2003 to 2009. He was a registered independent when Obama nominated him to be Treasury Secretary.

Taking cues from former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan who often used impenetrable jargon, Geithner deliberately spoke in “understated, nuanced, deliberately dull language that wouldn’t move markets or depress confidence,” as he later wrote. Despite persistent charges to the contrary -- including from allies of Warren -- he never worked at a bank or financial firm before the crisis. Nonetheless, he was ensconced in and a product of the economic establishment. He had a healthy dose of noblesse oblige and an earnestness about public service.

Warren came from a working-class family in Oklahoma that faced its own micro financial crisis when her father had a heart attack. She earned a debate scholarship to George Washington University, but dropped out to marry her high school boyfriend whom she later divorced. She ultimately graduated from the University of Houston and Rutgers Law School and worked her way up to the highest rungs of legal academia -- from teaching at the University of Houston to Harvard and becoming one of the country’s foremost experts on bankruptcy.

“Maybe this is what lots of people do who grow up with no money, but I’ll tell you this: I taught everything about money,” she declared at a recent rally in Seattle, explaining her zeal for teaching topics like bankruptcy and finance.

“The one thing you need to know about Elizabeth Warren is that you don’t get from Norman, Oklahoma, to where she is right now and take the journey she took without a steel spine and an indefatigability.”

—David Axelrod

She served on the National Bankruptcy Review Commission in the late ’90’s, and then watched Congress largely ignore the commission’s recommendations and pass a more pro-industry reform. Well before the crisis hit, she had often found herself fighting against the establishment Geithner represented. She spoke unapologetically and bluntly.

“The one thing you need to know about Elizabeth Warren is that you don’t get from Norman, Oklahoma, to where she is right now and take the journey she took without a steel spine and an indefatigability,” Axelrod says admiringly.

When the crash came, Warren saw a reckoning for a system she had long said was fraudulent and the chance to revamp it entirely. Geithner felt his first, second and third priority was to save that same system from collapse because then no other goals were possible.

“Old Testament vengeance appeals to the populist fury of the moment, but the truly moral thing to do during a raging financial inferno is to put it out,” he wrote. “The goal should be to protect the innocent, even if some of the arsonists escape their full measure of justice.”

In the fall of 2009, Geithner invited Warren and others overseeing TARP to the Treasury building for a briefing on the broader recovery efforts. At one point, Warren interrupted him to ask about the department’s response to the housing crisis.

“After the rush-rush-rush to bail out the big banks with giant buckets of money, this plan seemed designed to deliver foreclosure relief with all the urgency of putting out a forest fire with an eyedropper,” Warren wrote in her 2014 memoir, A Fighting Chance.

“We couldn’t fix the economy by fixing housing, but we could do the reverse,” Geither explained in his book, a sentiment he shared in a subsequent oversight hearing.

Geithner was also concerned about the politics of bailing out millions of people who were on the verge of being foreclosed on while the vast majority of people were managing to pay their mortgages on time.

The first Tea Party rallies had begun to spring up after a cable news rant by financial pundit Rick Santelli who focused on this point: “How many of you people want to pay for your neighbor’s mortgage that has an extra bathroom and can’t pay their bills?” he asked. “Honk if I’m Paying Your Mortgage,” with the Obama logo as the ‘o’ in “Honk” became a popular right-wing bumper sticker.

“[T]here were real fairness issues, as well as political issues, around using tax dollars to help their neighbors who got in over their heads,” Geithner wrote.

That perspective was particularly infuriating to Warren. She had spent much of her career trying to debunk what she called the “myth of the immoral debtor”-- essentially the stereotype that people in debt were spendthrifts and deadbeats when her research in bankruptcy courts showed that the majority of people facing bankruptcy were working class people struggling to hang on.

When Geithner explained his perspective on the issue at a fall 2009 meeting, Warren later wrote that she “felt as if one of us was standing on a snow-covered mountaintop and the other was crawling through Death Valley. Our views of the world -- and the problems we saw -- were that different.”

“The Two Warrens”

The 61-year-old Harvard professor and the 49-year-old Secretary of the Treasury were fighting over their seatbelts.

It was the fall of 2010. Obama had recently made his compromise appointment for Warren to stand up the CFPB which also meant Warren was moving into the Treasury building. The mood in the building was tense according to people in both camps, but Warren and Geithner each wanted to make it work.

On Warren’s first day, Geithner gave her a cop’s hat -- Warren had often referred to the CFPB as a “cop on the beat”-- and invited her out to lunch, as she recalled in A Fighting Chance.

“Put on your seat belt, Mr. Secretary,” Warren told him on their way to the restaurant.

Explaining that the car was bulletproof and the driver was well-trained with a gun, Geithner replied, “I don’t have to...We’re safe here.”

As the car sped along, Warren replied “What? Are you kidding?” She recalled that she may have raised her voice as she said: “What good is that if we get hit and this thing turns over a few times and you smash your head against that great bulletproof window?”

His seatbelt remained unfastened. (He fastened it on the way back from lunch, she noted.)

It was a bumpy start that got bumpier when someone anonymously told POLITICO that Warren’s new office was getting a fresh paint job and furniture, a makeover at odds with her populist brand. Geithner personally apologized to Warren for the report. “You could feel the frustration in the building when she was hired,” says one former Treasury official.

But as she came in and began working, some administration officials felt like there were “two Warrens.” In public, she was all righteous fury. In private, they say, they often saw a more reasonable figure.

Some administration insiders saw the “two Warrens” as proof of her hypocrisy. Her allies saw it as proof of her effectiveness. They note that her public rage had a strategic purpose and forced people to pay attention to her and her issues.

“They thought she was just doing it for publicity instead of doing it to create leverage to get in the room,” says one official who worked both at the CFPB and in the Obama administration. “She created an outside pressure base that allowed her priorities to be heard.”

Even those most critical of Warren say she brandished her pragmatism more than her populism while at Treasury, and say she was effective as a result. She readily brought in some top Treasury officials and her first hires for the consumer agency were a surprising mix of people from financial-services firms like Capital One and Morgan Stanley along with bureaucrats and academics. The Inspector General, whose job is to find problems, was rather complimentary of Warren’s tenure. Some ex-officials also say they were impressed at the administration skills of an academic with almost no management experience.

“She was very focused on talent and culture, talent and culture, talent and culture,” says the same official. Another former CFPB employee fondly remembered that when she had a baby, Warren’s gift was a baby-sized silver spoon -- a joking nod at her own soak-the-rich reputation.

Some Obama administration officials felt that Warren’s pragmatism in setting up the CFPB validated their own response to the financial crisis.

“She was meeting with the stakeholders, she was choosing her battles wisely,” says Axelrod. “It suggested to me that while there's no doubt that she is an ideologue in some ways and speaks in sort of these pugilistic tones that she also has an understanding that governing requires a different approach, a different set of skills.”

There is still some uncertainty, however, about how a President Warren would govern. “We don't really have a large enough sample size, because she's only run one thing, and she ran it for 10 months,” Axelrod says.

Obama v. Warren continued

The Warren-Obama brawls never really stopped.

After Massachusetts voters elected her to the Senate in 2012, Warren was far more wary of media but used her new platform to stay loud. She eschewed the playbook followed by Hillary Clinton and other new senators with a national profile, which was to lie low.

In 2013, she helped sink Summers’ nomination to be chairman of the Federal Reserve, a position he had long pined for and that, according to Axelrod, Obama had promised him at the outset of the administration. She followed that up with a 2014 memoir in which she wrote that Summers had warned her that she could either be an outsider or an insider but that the first rule of being an insider was not criticizing other insiders.

“I guess recollections differ,” Summers says now, in response to her depiction of his advice. “I’ve never before been accused of being biased towards going along to get along and I don’t think that was my advice. My recollection is that Elizabeth asked how her commission could have greater impact. I responded that if they sometimes praised something that was done they would have more impact than always excoriating policy makers.”

In late 2014 and early 2015, she almost single-handedly killed Obama’s nominee for the undersecretary of domestic finance, Antonio Weiss.

“Enough is enough,” she wrote in a scathing Huffington Post piece attacking Weiss’s work in the private sector particularly on corporate inversions. Her opposition was rooted in her broader critique of the administration that began during her time as a TARP watchdog.

“It’s time for the Obama administration to loosen the hold that Wall Street banks have over economic policy making. Sure, big banks are important, but running this economy for American families is a lot more important,” she wrote.

Some administration officials again saw what they considered opportunistic grandstanding. “It made Treasury less effective and it hurt President Obama,” says one former White House official.

And Obama vented his frustrations with Warren publicly when it came to the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal and the fast-track authority he wanted to negotiate it.

“Elizabeth’s a politician like anyone else,” Obama said in 2015, adding that her arguments “don’t stand the test of fact and scrutiny.”

The comments drew a rare public rebuke from Ohio’s Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown, a TPP opponent, who said “I think the president was disrespectful to her” and that Obama “has made this more personal than he needed to.”

Even in the final weeks of the presidential race in 2016, when most Democrats were closing ranks, Warren wrote to Obama urging him to unilaterally replace his chairwoman of the SEC, Mary Jo White, with another SEC commissioner. Warren had been feuding with White since 2015 when she wrote a 13-page letter to the SEC chair bluntly telling her that “to date, your leadership of the Commission has been extremely disappointing.”

The Obama administration had repeatedly defended White but Warren wrote to Obama that “Chair White's extraordinary, ongoing efforts to undermine the agency's central mission make such a step necessary.”

One former Treasury official says people in the department were glad Warren addressed the letter to Obama so he could finally understand what it was like to have to deal with her on a daily basis.

The president didn’t budge.

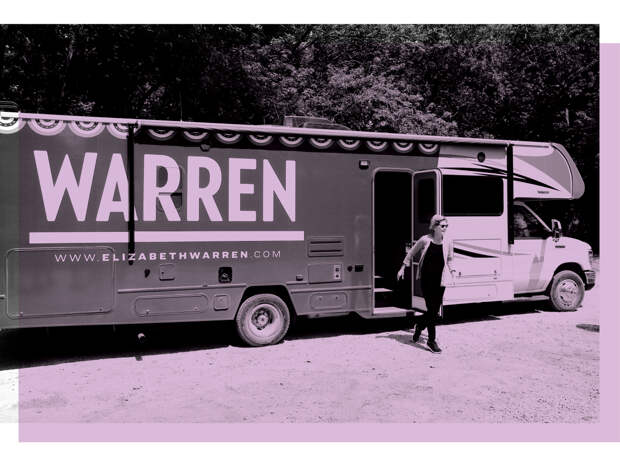

The Warren Winnebago

Three years later, Warren is casting herself as the standard-bearer of the party Obama once led.

In rural Western Iowa, she is sitting in a Winnebago with “HONK IF YOU’RE READY FOR BIG STRUCTURAL CHANGE” printed on the back. When one person honks during a 30-minute drive, Warren yelps “We got ‘em! They honked! Big structural change! Yes!”

With a Starbucks venti iced tea in hand and a half-eaten banana on the table, Warren looks cool in a thin, light pink cardigan despite just finishing an hour walk in the hot sun surveying flood damage in Pacific Junction. The Winnebago is stocked with healthy snacks including Boom Chicka Pop, Avocados, Cheez-It Extra Toasty and BelVita crackers. There are some cookies with "PERSIST" written on them from a devoted fan with a bakery along with Michelob Ultras in the fridge. An aide stands by the fridge door because it wildly swings open every time the Warren Winnebago turns too sharply to the left.

Don’t go too far to the left, the reporter jokes, lamely. Crickets from Warren and her aides.

She is talking about how she witnessed firsthand, in the Obama administration, how powerful institutions had more access to power than those most affected by the crisis.

“Who comes into the office of the Secretary of Treasury? Who comes in to the Federal Reserve Bank to plead their case? Who's on the phone with the top economic advisors?” she asks rhetorically.

“It's not the poor guy down the street who's been cheated on his mortgage and is six days away from the sheriff coming and moving him and his kids out on the sidewalk. And that's -- that's how the system is rigged...They have 1000 points of access to every decision maker in Washington. And regular families, they got none. They got nothing. And that, that, tilts every decision, every day, just a little bit.”

Warren insists that she doesn’t question the motives of the people who served in Obama’s Treasury Department. But asked if she thought they had been “sort of captured by the system--” Warren jumps in: “That’s it. They just they saw the world differently. They had spent all their time with giant banks and their representatives. This is my point about how Washington works.”

Such broad-brush comments inflame former Obama advisers. Many regard her as insufficiently grateful to Obama and Biden and others in the administration.

“Elizabeth Warren would be a beloved Harvard Law Professor not a presidential candidate if @barackobama and @JoeBiden had not worked with her to make her idea to form a consumer financial protection bureau law,” former White House communications director Jen Psaki

Beyond the question of her loyalty, some question the soundness of her ideas. Summers, for one, has co-written two op-eds arguing against the underlying math in Warren’s wealth tax, the central means for how she says she will pay for her ambitious liberal agenda.

While many on the Obama team take issue with agenda items such as imposing a wealth tax and furthering trade protectionism, they wonder if Warren, in the Oval Office, would more closely resemble the pragmatic figure who reached out beyond her inner circle to set up the CFPB.

"The global political world is filled with people who capitalize on anger and she has," summed up one former Obama official, who recalled her as a “demagogue” on TARP.

Begrudgingly, however, the official and several others say they have gained some new respect for her by watching her closely on the presidential campaign trail.

"I certainly like this Elizabeth Warren more than the Elizabeth Warren of that era."

—former obama official

“Ironically, and I give her credit on this, part of the reason she’s doing well politically today is that she has put forward plans that have details,” the former official says. “I certainly like this Elizabeth Warren more than the Elizabeth Warren of that era."

But the differences between the two camps may be difficult to bridge. Were she to get the Democratic nomination, the ex-Obama team may rally around Warren to defeat Donald Trump, but some worry about what she would do if confronted with an economic crash of her own.

"Financial crises are not morality plays,” says Summers. “Senator Warren was right and made a huge contribution by pushing for the CFPB but the idea that once crisis took hold you could resolve it from the bottom up was unrealistic and would have been catastrophic if attempted."

Article originally published on POLITICO Magazine